This project’s conclusion not only ushered in a new age in medicine, but it also resulted in notable advancements in DNA sequencing technology. The goal of the 13-year, publicly sponsored Human Genome Project, which began in 1990, was to identify the DNA sequence of the full euchromatic human genome in 15 years. Many people, both scientists and nonscientists, were skeptical about the Human Genome Project in its early stages. Whether the project’s enormous expense would offset its possible advantages was one of the main questions. But today, it’s easy to see how successful the Human Genome Project has been.

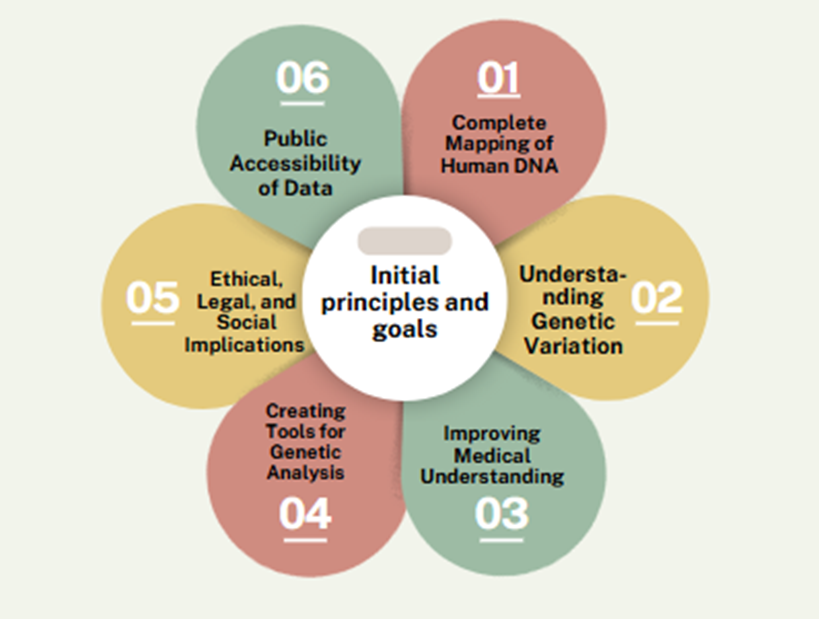

Initial Principles and Goals of the Human Genome Project

Since its inception, the Human Genome Project has been guided by two basic principles. First, it welcomed partners from any country to cross borders, build an all-inclusive endeavor to better comprehend our shared molecular history, and benefit from varied methods. The collection of publicly financed researchers that finally formed was known as the International Human Genome Sequencing Consortium (IHGSC). Second, this effort stipulated that all human genome sequence information be made freely and publicly available within 24 hours of assembly. This foundational premise maintained unlimited access for scientists in academia and industry, as well as the ability for researchers of all types to make speedy and unique discoveries.

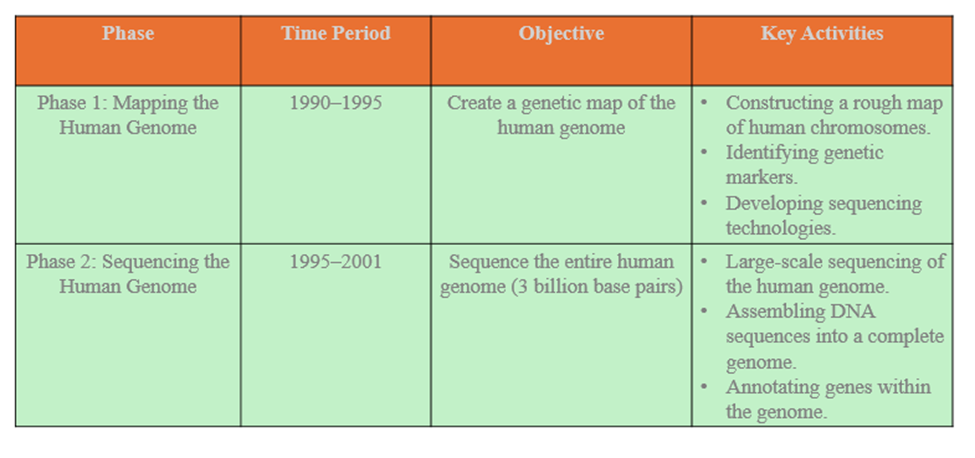

Phases of the Human Genome Project

Based on the insights garnered from the yeast and worm research, the Human Genome Project utilized a two-phase method to tackle the human genome sequence. The first phase, called the shotgun phase, separated human chromosomes into DNA segments of an acceptable size, which were then further subdivided into smaller, overlapping DNA fragments that were sequenced. The project’s second step, known as the finishing phase, involved filling in gaps and resolving DNA sequences in confusing places that had not been collected during the shotgun phase. The shotgun phase resulted in 90% of the human genome sequence in draft format.

Who carried out the Human Genome Project?

The Human Genome Project would not have been completed as swiftly or successfully without the dedicated participation of a global consortium comprising thousands of researchers. In the United States, the researchers received funding from the Department of Energy and the National Institutes of Health, which established the Office for Human Genome Research in 1988.

Researchers from 20 different universities and research institutes in the United States, United Kingdom, France, Germany, Japan, and China collaborated to sequence the human genome. The International Human Genome Sequencing Consortium was formed by groups from these nations.

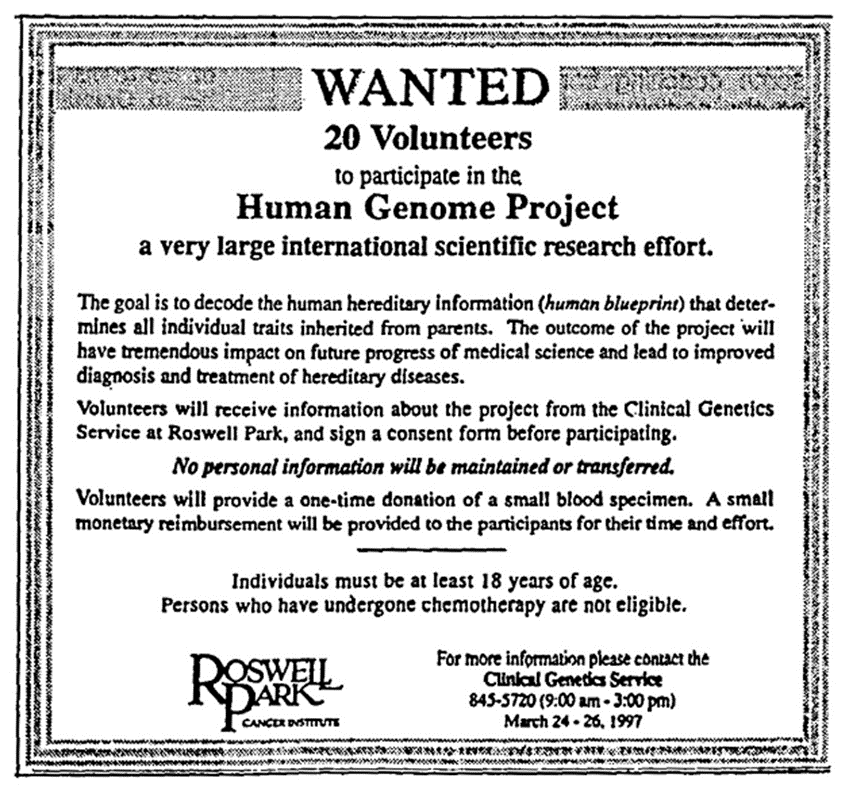

DNA collection for the Human Genome Project

The majority of the initial human genome sequence was collected from volunteers in Buffalo, New York, with experts at the Roswell Park Cancer Institute managing DNA preparation and sequencing. They contacted potential donors through public advertisements, acquired informed consent, and took blood samples to extract DNA. The Human Genome Project’s sequence was mostly based on one individual of blended ancestry, who contributed 70% of the reference genome with the remaining 30% coming from 19 others, mostly of European heritage.

(NHGRI History of Genomics Program Archive)

From Rough Draft to Final Form

After completing the draft phase of the Human Genome Project, the International Human Genome Sequencing Consortium (IHGSC) began the finishing phase, which corrected gaps and clarified confusing DNA sequences. During this phase, 99% of the human genome was completed, with 2.85 billion nucleotides and a low error rate of one in 100,000 bases. The number of gaps reduced dramatically, from 147,821 to 341, with the majority occurring in complicated chromosomal areas. Initial estimates of up to 40,000 protein-encoding genes were reduced to 20,000–25,000. Future difficulties included discovering genetic variants associated with diseases and investigating functional parts throughout the genome.

From Digital Information to Molecular Medicine

The Human Genome Project demonstrated that human nucleotide sequences are 99.9% similar among individuals, yet even a single nucleotide alteration can lead to disease. This knowledge has greatly improved our understanding of many diseases, combining cytogenetics and genomic data to provide deeper insights. However, the expected speedy identification of new medicines has not resulted just from knowing the genome sequence. Efforts are currently concentrated on understanding the protein products encoded by genes, as mutations frequently result in faulty proteins. The discipline of proteomics is critical in this attempt, and researchers are also looking into non-coding sections of the genome. More linkages to human disease are likely to emerge as we continue to evaluate genomic data.

Cost of Human Genome Project

The Human Genome Project was previously estimated to cost $3 billion over a 15-year period. While precise cost accounting was difficult to implement, particularly among overseas funders, most agree that this rough estimate is close to the correct number.

Did the Human Genome Project produce a perfectly complete genome sequence?

No. Throughout the Human Genome Project, researchers continuously improved DNA sequencing techniques. However, they were limited in their ability to determine the sequence of certain regions of human DNA.

In June 2000, the International Human Genome Sequencing Consortium reported that it had completed a draft human genome sequence that included 90% of the human genome.

In April 2003, the consortium stated that it had created an essentially complete human genome sequence, which was greatly enhanced over the draft. It accounted for 92% of the human genome and had less than 400 gaps, making it more precise.

Celera and Human Genome Project

Before the IHGSC finished the first phase of the Human Genome Project, Celera Genomics, led by Dr. Craig Venter, planned to sequence the entire human genome in three years. Celera created a dataset of 27.27 million DNA sequence reads from five individuals, with an average of 543 base pairs. In contrast, the Human Genome Project offered second data obtained from BAC contigs, resulting in 16.05 million sequence reads.

Celera used two primary assembly methods: whole genome assembly and regional chromosome assembly. Both approaches allowed for direct data comparison, yielding results that were very similar to the IHGSC. In February 2001, both groups published versions of the human genome at the same time, finishing their work ahead of schedule thanks to breakthroughs in sequencing technology and collaboration.

Summary

The Human Genome Project was successfully completed in 13 years by a collaboration of public and private researchers. Despite using a variety of approaches in their research, these scientists arrived to the same conclusions. In doing so, the researchers not only quiet their opponents, but they also completed the project two years earlier than expected. Perhaps more importantly, these scientists sparked a continuing revolution in our fight against human disease and presented a fresh vision of the future of medicine–albeit one that has yet to be fully realized.

Refrences

Collins, F. S., Patrinos, A., Jordan, E., Chakravarti, A., Gesteland, R., Walters, L., & members of the DOE and NIH planning groups. (1998). New goals for the US human genome project: 1998-2003. science, 282(5389), 682-689.

Collins, F. S., & McKusick, V. A. (2001). Implications of the Human Genome Project for medical science. Jama, 285(5), 540-544.

Gibbs, R. A. (2020). The human genome project changed everything. Nature Reviews Genetics, 21(10), 575-576.

Moraes, F., & Góes, A. (2016). A decade of human genome project conclusion: Scientific diffusion about our genome knowledge. Biochemistry and Molecular Biology Education, 44(3), 215-223.